Chronic, Progressive, Ultimately Fatal

Chronic, Progressive, Ultimately Fatal

For decades, the problematic way people used alcohol and illicit drugs was defined as being “chronic, progressive and ultimately fatal.” In fact, some of the earliest approaches to treat addiction included crude ultimatums like, “Get sober or die.” Early on in my career, when a client participating in an inpatient rehab program was unmotivated, difficult and distracting from others in the program, addiction counselors would ask that client to leave treatment, telling them to “go do some more research and come back when you are ready.” This meant go out and continue to drink or use drugs, and when they were truly ready to get sober come back.

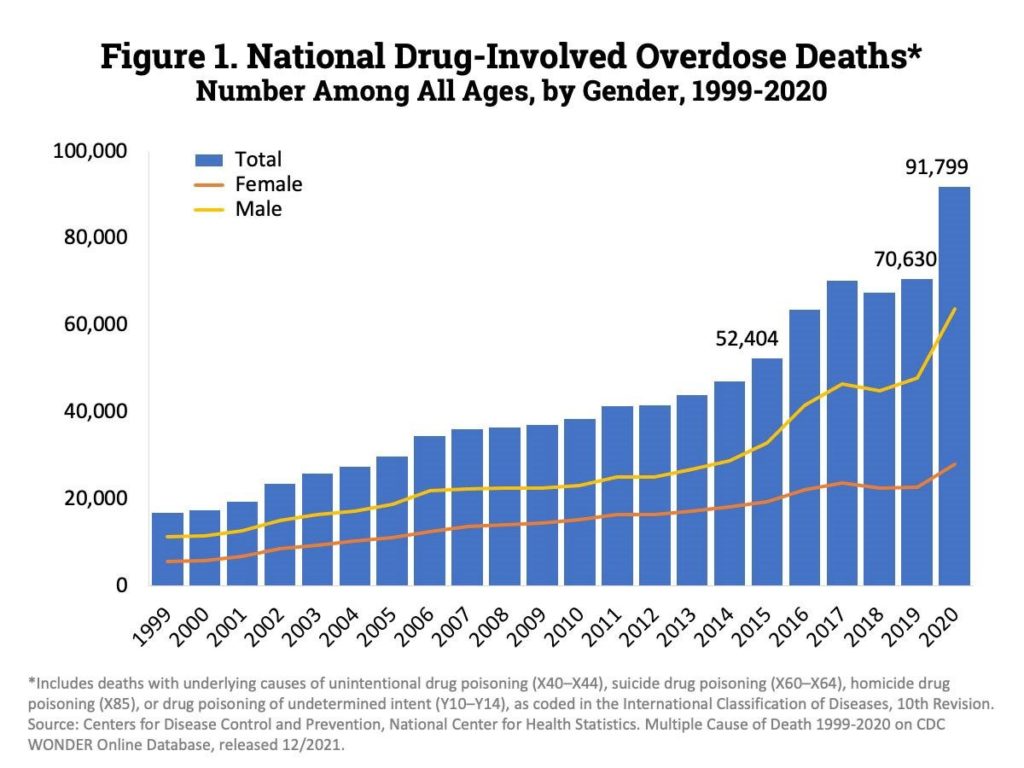

Back then the drugs weren’t nearly as deadly as they are today. The urgency for change now is of paramount importance. When we consider how the potency of drugs has increased, along with the introduction of Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is up to 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, the time frame for addiction as chronic, progressive and ultimately fatal has gone from months and years to days and weeks. Overdose deaths continue to rise at a staggering rate, leading to a health crisis.

This is why the harm reduction approach to treatment for substance use disorders is on the rise. The goal of harm reduction is to prevent overdoses, and save lives. I would argue, however, that the treatment field has gone so far down this trail to save lives, that they have lost sight of the most important part—restoring lives. The treatment community has become so hyper focused on reducing overdose deaths that they have empowered individuals with substance use disorders to continue using (more safely), largely maintaining a status quo of in terms of quality of life.

Our latest and most progressive approaches to harm reduction include setting up safe places where individuals can safely use their drugs while being monitored for overdose. In Canada, they are testing programs that actually prescribe heroin for people to use, again while being monitored. These programs can reduce death. But what about the restoration of a meaningful life? When we remove potential consequences, do we not also remove incentive for change?

The harm reduction approach seems to convey the message that we can’t stop people from drinking or drugging, and as a treatment community we should empower individuals to make their own choices about use. In such cases, we ignore the fact that chronic substance abuse has a reason and purpose, and without help to understand the purpose of substance use, we are continuing to see harm in the lifestyle, while avoiding death. In short, we are not preventing death, but only delaying it.

Restoration of a meaningful life in recovery has become a “pie in the sky” goal rather than a worthwhile endeavor. Those suffering from addiction are excused for their unhealthy behavior and told many believe that they don’t have the capacity to make healthy choices due to their addiction, so we will help them make the choice to stay alive by providing safe-using sites.

The currently popular harm reduction approach to addiction does not focus nearly enough on recovery and restoration of meaningful productive lives while steering efforts towards reducing fatalities. We need to update the old adage of “Chronic, Progressive and Ultimately Fatal” to include “To restore meaningful and purposeful lives.”

I have added “to restore and purposeful lives” to raise the level of importance of change. In many cases traditional treatment programs, we have punted on the idea that meaningful and purposeful lives are possible with help, support and change. Those who have retained the belief that true sobriety is the goal and recovery is possible, encourage those suffering with addiction, rather than being a source of discouragement that our goal is merely to avoid death. When your loved one enters treatment, I am confident that it is your hope that they arrest the problem, rather than manage it. Yet substance abuse professionals who value the quality of a meaningful life are now often scorned, and are targeted for not accepting that change will happen when the individual is ready. Our sense of urgency for change has been replaced by let’s keep them alive, and when they are ready for change, we will be there. But the evidence speaks to how frequently the desire for change doesn’t come.

Reducing deaths is important. Restoration of a meaningful and purposeful life is not something to be put off to for the future, and requires equal standing in the fight for life for those suffering from addiction.